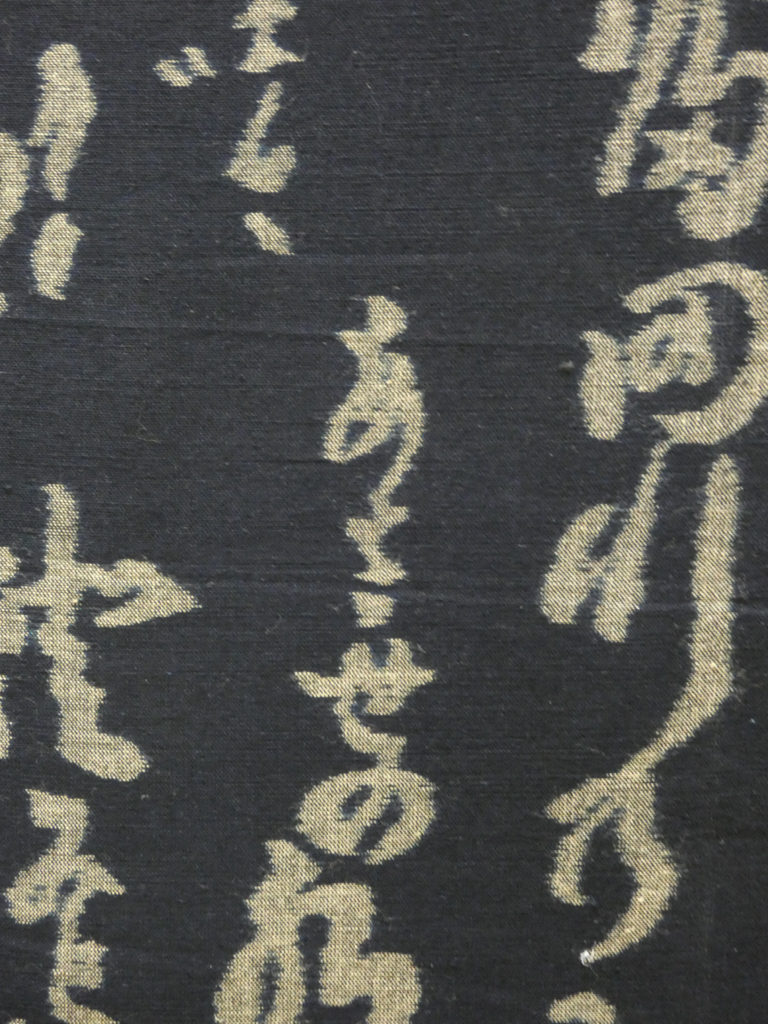

Starting in July of 2021, I’ve been helping the Bombshells of Cincinnati with an installation in Washington Park called COSY CURIOSITIES. I was recruited by Judy Dominic to be a “sidekick” and assist with knitting and crocheting various components. Each week I would go to a certain porch and pick up a project kit containing yarn and a slip of paper with instructions like “knit or crochet a rectangle 18″ x 36″ with lots of texture” or “latch hook this piece between the black outlines.” One of my favorites included 3 big balls of yarn, a knitted heart pattern and instructions to “make as many hearts as possible.” And I never knew how my pieces of the project fit into the whole. I would drop off finished pieces and pick up kits each week. The whole experience was mysterious and magical and it was just what I needed through the ups and downs of the pandemic. People would ask me what I was making, and I would say “I don’t know!” and tell them about the magical porch and the Bombshells.

The COSY CURIOSITIES art installation is currently up and was timed to cheer things up for Mittenfest–an event featuring craft beers, food trucks, a dj and more (February 19 and 20th). The Bombshells also recruited local makers to create hundreds of pairs of mittens to donate give away to charity groups that work with people in need.

I have been making Yarn Bomb Kits to sell. These kits are pre-made, ready to install bits of whimsy and delight and I hope they go out into Cincinnati and make many people smile! They are perfect for non-yarn artists to brighten up their homes, yards or neighborhoods. Of course if you knit or crochet, do your own and brighten up Cincinnati this winter! The Fiber Art Market scheduled for Jan. 29 & 30 was cancelled, so I’m not sure where or when I will be selling them, but I’ll edit this post when I know!

Here’s what you need to know:

- Choose your location. You can install on many different surfaces. I suggest starting easy with a pole or chain fence (chain link will give you the most options, but wrought iron or narrow pickets or farm fencing could work too. Choose a location near your home or work–you want to be able to check on your piece. You can re-secure it if it’s sagging or falling off and remove it when it gets to be more of an eyesore than an eye-delight.

- Get permission–it’s a good idea to ask if possible. The property owner may remove it or ask you to install it in a certain way so you don’t cause damage. Be especially careful of trees. Prolonged covering of trees with slow-to-dry knitted/crocheted fabric can cause fungus to grow. It’s safest to dress your own trees (for a short time period) or get permission before dressing someone else’s tree. Or just decorate poles.

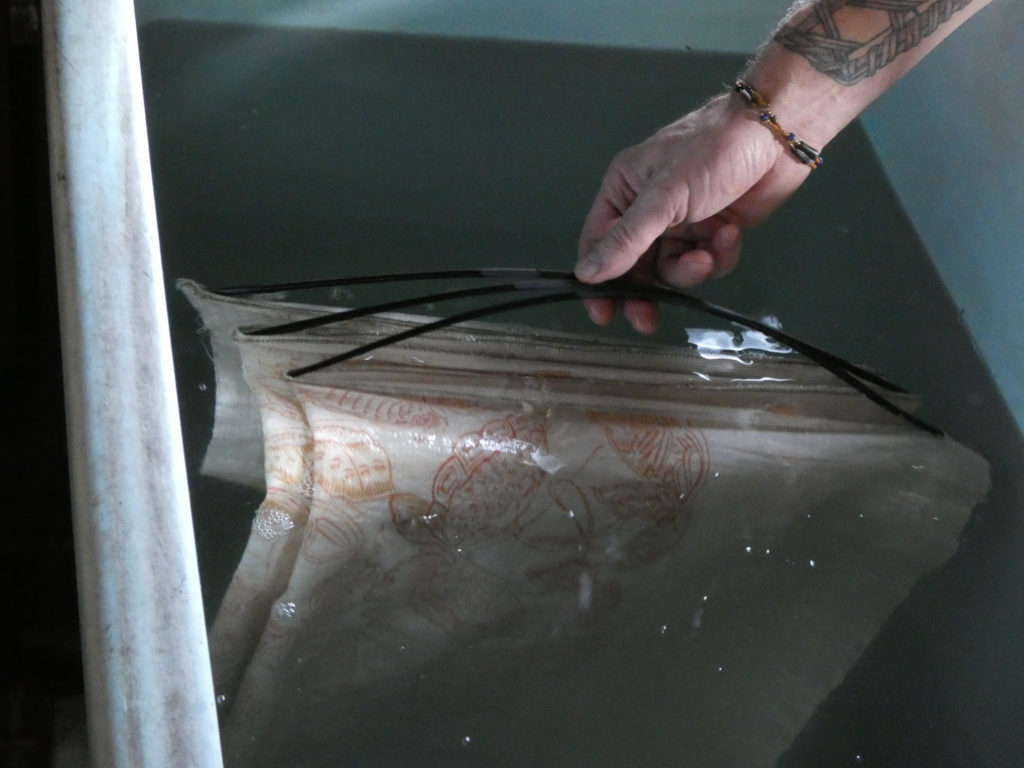

- Installation – this depends a lot on the size of your piece and the surface you’re attaching it to. You can sew or tie your pieces onto fences, trees and posts, or use plastic cable ties.